Figuier Sauvage à Versailles – A Journey of Scent and Light

The journey from Grasse to Versailles began before dawn — a short train ride to Cannes, and then 6 hours to Paris. I love the train- it’s peaceful compared to flying, and always full of international travellers. This time, I was surrounded by a group of 34 boisterous middle-aged Australians. From Paris, I took the subway, then an Uber, and by the time I finally reached my hotel in the village of Versailles, the sky had opened; rain fell in silver sheets, soaking the cobblestoned streets. I changed from flats to heels, fastened my silver jewellery — a quiet wink to Paco Rabanne — and stepped back out into the evening light of the fading storm.

Arrival in the Rain

It felt almost cinematic: the scent of wet stone, the last drops falling from the chestnut trees, and the sunlight beginning to return. Versailles revealed itself like a dream — the ancient cobblestones gleaming in the evening light, the air luminous.

As I arrived to the front of the exhibition venue, I passed Thomas Fontaine, president of the Osmothèque, standing in conversation with his companion. There was a brief flash of tension between them, a curt « Mais tu te calmes ! », and as he stormed away, I caught her eye with a half-smile and a soft, conspiratorial « Ohlala, les hommes… » She smiled back — a tiny moment of female complicity amid the grandeur.

Inside, the space was already alive with movement. I was the last perfumer to arrive — though, curiously, I had been told precisely to come for six o’clock. The others’ installations were finished, their perfumes ready to mist gently into the air from elegant glass bulbs. My bottle, as it turned out, had a crimped spray top instead of the required screw cap. No one had mentioned this detail. A small wave of mild chaos followed — a few raised eyebrows, a dash of improvisation — and then Matthieu, the sweet and eccentric event organiser, laughed, « Ça va, la vie est belle ! » and ran outside with my bottle to fill the dispenser himself.

By the time it was installed, I was finally able to exhale. Figuier Sauvage had found its place among the portraits. The rain had stopped, and the air smelled faintly of wet wood, stone, and perfume — the perfect prelude to the evening ahead.

The Exhibition and the Unexpected

The exhibition opened with speeches: Thomas Fontaine spoke first, followed by the mayors of Versailles and then Grasse, and several representatives from the Osmothèque and Grasse Expertise. Then the crowd began to circulate, champagne glasses in hand, as the first notes of perfume mingled with the sound of voices

Each installation paired a black-and-white portrait of well-known personalities with a fragrance created by an individual perfumer, each having been given creative freedom to create their own dialogue with the faces captured by the talented photographer. Mine was to accompany a photograph of Paco Rabanne surrounded by tarot cards — a concept I had loved for its esoteric symbolism. Instead, I discovered that the portrait chosen for event was another: a striking close-up of his face, in luminous grayscale. In the end, it felt somehow right — more human, more direct — as if the perfume no longer needed the mystic props to tell its story.

I remember saying to someone nearby how refreshing it was to see true photographic prints again, with their depth and silver light. Our eyes, I said, are no longer accustomed to that kind of image — digital screens have flattened our sense of texture and nuance. These portraits reminded me how much beauty resides in the tangible.

And there, beside the portrait of Paco Rabanne, stood my perfume — Figuier Sauvage — its soft green radiance rising quietly into the air.

The Aura of Paco Rabanne

Not long after the speeches concluded, I met the photographer, Elias, who had captured the portrait that now hung above my perfume. A tall, gentle man with an attentive gaze, he carried the quiet assurance of someone who has spent a lifetime observing others. We spoke at length about Paco Rabanne — not the public legend of metal dresses and architectural futurism, but the private man behind the myth.

He told me that Paco was profoundly spiritual. During their sittings, he would sometimes pause mid-conversation, look at the space around the photographer’s head, and say, almost matter-of-factly, “Je vois ton aura.” The photographer said it was never performative, never eccentric for the sake of it; Paco truly saw what he described, and lived by what he felt. He spoke of energy, of light, of invisible design — as if his work in metal and fabric were simply the visible echo of something cosmic he perceived all around him.

Listening to these recollections, I understood again why I had chosen the fig tree as my inspiration. The fig — that paradox of a fruit that is also a flower turned inward — embodies the same hidden radiance. It’s humble, rooted, yet filled with mystery; a symbol of knowledge, abundance, and spiritual fertility. I realised that my composition had unconsciously mirrored his vision: a fragrance of sunlight filtering through rough sweet-smelling leaves, of wood warmed by skin, of sweetness concealed at the heart of shadow.

Around us, the gallery pulsed softly with conversation and scent. Guests leaned in to inhale each perfume, to compare impressions, to whisper discoveries. Yet for a few minutes, time seemed suspended — two people standing before a photograph, speaking quietly about invisible things: light, spirit, and the unseen architecture of beauty.

The Human Encounters

As the evening unfolded, the space filled with guests— the clinking of glasses, the gentle hum of conversation, the soft cloud of perfume lingering above it all. I mingled with the crowd, and soon found myself surrounded by familiar faces from Grasse — perfumers, writers, students, and friends I hadn’t seen in years. It felt like a small reunion within a larger celebration, a gathering of those who share the same rare language of scent.

There was a sense of quiet pride, too, in seeing the community of Grasse so present in Versailles — the cradle of French culture meeting the cradle of perfumery. We spoke of raw materials, of education, of the long-awaited bridges now being built between these two historic worlds.

One of the perfumers present, an instructor from ISIPCA I believe, approached me with curiosity. He told me that Figuier Sauvage was his favourite perfume in the exhibition — that it felt atypical, unpredictable, and yet perfectly balanced. He said that while many compositions were pleasant, mine surprised him; it had something alive in it. He laughed and teased that he might run it through a GC, but I knew it was simply admiration and curiosity in his tone.

Later, a man from the public — French, perhaps fifty — stopped in front of the portrait and remained there for a long time. He introduced himself as an artist, spoke passionately about the state of the world, about nature, and even about artificial intelligence. He was eccentric and fascinating. When he smelled Figuier Sauvage, he paused and said, “I haven’t worn perfume in decades, but this… this I would wear.” I offered him one of the small minis I had prepared, wrapped in white tissue paper. He opened it immediately, dabbed some on his wrist, and smiled. It was such a simple, human exchange — the kind of moment that justifies the long hours alone in the lab.

Several others came to speak to me — a radiant couple from Paris who described the perfume as “like standing beneath a real fig tree in summer — living, complex, and warm.” A few bloggers and journalists I knew drifted by, notebooks and cameras in hand, some surprised to see me, others happy to reconnect. Other perfumers, of course, (as there were 24 of us), mingled and observed with interest how guests would interact with their creations.

By the end of the night, I felt deeply content — not triumphant, not proud, but quietly fulfilled. My perfume had found its audience. It had spoken on its own, and it had been understood. That, for me, is success.

Reflections on Creation

As the evening drew to a close, I lingered in the gallery for a few last moments, watching people move from portrait to portrait. I thought again of what the photographer had said earlier — that every one of the great personalities he had photographed, from actors to designers to artists, shared one defining trait: intelligence. Not the cold, strategic kind, but a luminous intelligence — perceptive, present, curious. He said that despite their fame, they were all simples — grounded, authentic people, and kind. And it made me think about how often sensitivity and intelligence walk hand in hand, disguised as humility.

Perhaps that’s why certain creations — a portrait, a melody, a perfume — resonate so deeply. They carry the vibration of an active mind and an open heart working together. I realised that Figuier Sauvage had been born from that same impulse: curiosity married to intuition, intellect softened by empathy.

The next morning, leaving Versailles, that reflection stayed with me. My Uber driver to Gare de Lyon was a young man from Cameroon — tall, elegant, articulate. We began talking about perfume, of all things; he told me he loved discovering niche fragrances, that scent for him was a form of self-expression. From there, our conversation leapt to culture, to language, to the way we measure intelligence. I told him that I could tell he was very intelligent — because he listened, he asked, he connected ideas. He smiled, a little surprised, as if no one had ever said that to him before. It reminded me that sometimes intelligence doesn’t announce itself loudly; it reveals itself in curiosity, kindness, and the courage to wonder.

When I reached the station and boarded the train back to Grasse, I felt profoundly grateful — not only for the exhibition, but for every small human exchange that had woven itself into the journey. From the photographer’s quiet wisdom to a stranger’s spark of insight, it all became part of the same story.

Figuier Sauvage had not just been smelled — it had been felt, mirrored, and shared. And as the train sped south through the rain-washed countryside, I realised that this — the meeting of minds, the subtle touch of connection — is the truest language of perfume.

Coda – Versailles at Dawn

The morning after the exhibition, I rose early and walked through the quiet streets of Versailles. The air was fresh and cool, touched with the faint scent of rain from the night before. I hadn’t realised, until I began to walk, that my hotel was barely five minutes walk from the Château itself.

And then, suddenly, there it was, at the end of an ordinary tree-lined street — vast, gilded, and gleaming in the morning light. The gold of the gates and rooftops caught the sun so fiercely it seemed lit from within, as if the palace itself was lit by neon lights. The cobblestones sparkled underfoot. Around me, the town was still half-asleep on the Sunday morning — the sound of a few bicycles, the murmur of café cups being set on terraces.

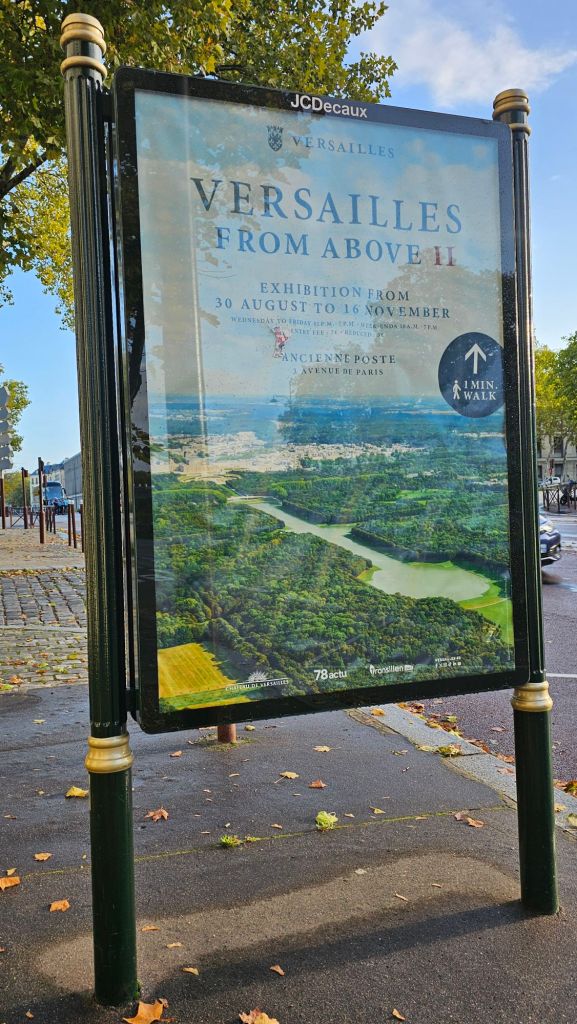

I walked only as far as the great open esplanade before the palace. Beyond the expansive buildings stretch the fabled gardens — acres upon acres of green, the perfumed realm of jasmine, roses, and tuberose that the mayor had mentioned in his speech the night before. I didn’t have time to enter, only to stand there knowing they were there — fragrant, hidden, waiting. A poster nearby showed an aerial photograph of Versailles From Above, revealing the full expanse of that geometric paradise, its avenues unfurling like ribbons of light.

I promised myself that next time, I would return just to walk those gardens — to follow the ghost of Marie Antoinette through her flowering labyrinths, to smell the same air she once breathed. Even standing at the gates, I felt the aura of that world — a quiet magnificence that seemed to hum beneath the surface of things.

There was a sense of lineage in it all — the art of French perfumery, the culture of beauty, the belief that refinement and imagination can coexist. As I turned back toward the station, the sun climbed higher, gilding everything in sight. I carried that light with me — the gold of the gates, the scent of fig and wood, and the echo of all those invisible connections that perfume makes visible.

Epilogue – The Return to Grasse

The train from Paris sped south through the green fields damp with rain, the landscape softening into the familiar palette of Provence — olive trees, terracotta, and that certain Mediterranean light that always feels like home. I watched the countryside unfold and thought about how far this path has carried me: from a small atelier in Grasse to Versailles, from the solitude of the creation process to a public exhibition of such stature.

Figuier Sauvage began as a study of light through leaves, a meditation on nature and spirit. In Versailles, it found its voice among others — not louder, but distinct, rooted, alive. I realised that everything I’ve done — every quiet decision, every refusal to compromise, every long night in the lab — has been part of a slow, patient pilgrimage toward this moment.

When I stepped off the train in Grasse, the air was warm, filled with the scent of fig leaves drying in late summer sun. I smiled, knowing that in some small way, the dialogue between Grasse and Versailles had been renewed — not through institutions, but through a single perfume born of love, curiosity, and light.

Postscript – On Visibility and Value

If I have one regret from the event, it is that no one thought to gather us — the perfumers of Grasse — for a simple group photograph. We were, after all, the ones who had travelled there, at our own expense, to represent the living art of our city. Yet amid the speeches and photo opportunities, it seemed the cameras turned mostly toward officials and administrators, not toward the perfumers whose creations made the event possible.

It’s an old story, perhaps, but one worth naming. Perfumery, like photography or music, thrives only when those who create are given the same visibility as those who administer. Institutions may preserve heritage, but artists embody it — and without us, there would be nothing to celebrate.

The exhibition is open until November 29th, 2025

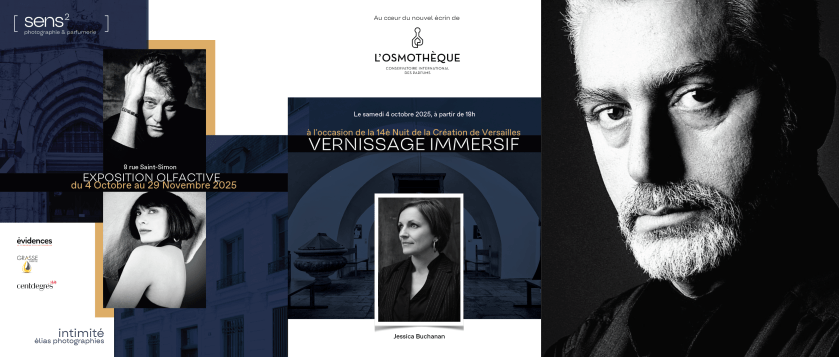

EXHIBITION: SENS² — Photographie & Parfumerie

Osmothèque, Versailles

October 4 – November 29, 2025

Opening Night: Saturday, October 4 at 18h

Leave a comment